A reflection on the role of artistic expression in the Pride Movement

A reflection on the role of artistic expression in the Pride Movement

Elizabeth Richmond-Garza, PhD

Director and Graduate Adviser, Comparative Literature

UT Regents’ Distinguished Teaching Associate Professor, English

Affiliate Faculty, Middle Eastern Studies | Human Dimensions of Organizations

June 28, 2021

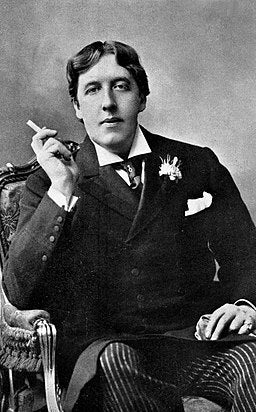

When Oscar Wilde, a gay Irishman living as a straight writer and personality in London, was sentenced to serve two years of hard labor in prison on 25 May 1895 for violating an anti-sodomy law that was only repealed in 1967, his trial began not with evidence of acts he had committed but instead with an accusation of “posing,” of seeming to be the sort of person who could break the law. We might imagine in Pride Month 2021 that defining someone based upon our impression of their appearance would be part of a history lesson rather than our daily lived experiences. However, whether in relationship to gender and sexuality or the many other intersectional issues which define each of us, how we appear to others often determines how we are permitted to live. While we all have complex personalities under the surface, we are never fully able to share them, even with those closest to us, let alone in public or in the workplace.

What I am suggesting is that Wilde’s Victorian world and our own are not as different as we might immediately think. Obsessed with appropriate dress and behavior, and uneasy about how to function in an increasingly diverse and globalized world, Wilde’s contemporaries share our concern with appearances, profiling and branding. When, using the new technology of the camera in the 1880s to create composite photographs of the children of recent Jewish and Irish immigrants and comparing them to ones of recently convicted felons in London, Sir Francis Galton anticipated both the charms of tagging someone on social media and the dangers of racial profiling, a topic of global concern again since the summer of 2020. Western thought has consistently relied upon sight and sensory information for verification, and yet a simple cliché like “seeing is believing” reveals a real problem. While we receive information from our senses, we construct our view of the world based upon our beliefs and values, that is to say based upon bias. When we observe a coworker, we evaluate them relying on what they are doing, saying, wearing, etc. framed within social conventions and norms. If we are puzzled by something, we fill in the blank with our previous experiences and our current expectations and desires.

Unknown photographer, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

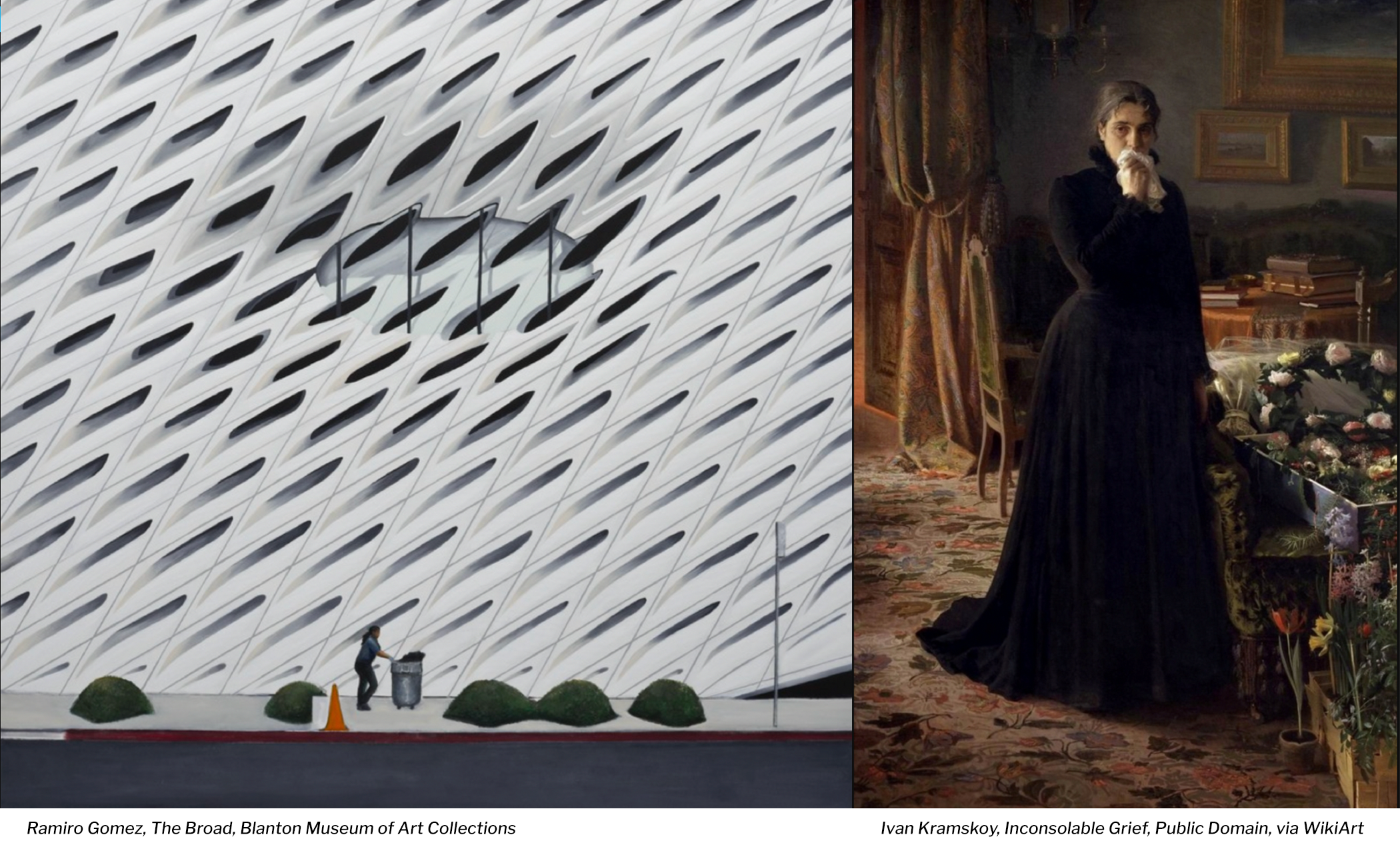

In 1956 Erving Goffman invited us to see how we behave and interact with each other in “everyday life” as similar to a theatrical performance, organized according to roles, scripts, social and physical spaces, and expectations. While each of us has an identity, it is mediated by the environment and the rest of the cast. We must choose to conform or break expectations regarding everything from choice of attire and body language, to accent and management style. Using artistic images of human beings as a sandbox allows us to experience and reflect on how we read and misread each other in social settings. It opens a space for humility, empathy, and care. There is much we will never know about others, as we can never feel as they do, but we have an ethical obligation to be mindful. Ivan Kramskoy’s understated 1884 painting, “Inconsolable Grief,” in the Tretyakov Museum in Moscow reminds us that some pain, in this case the deaths of his two children, may be expressed quietly by the grieving mother in the image or through work by a father grappling with their shared loss. In a 2016 canvas, Ramiro Gomez asks visitors to UT’s Blanton Museum to notice the BIPOC people we overlook each day, creating an image of an unidentifiable figure pushing a garbage bin in front of the distinctive facade of “The Broad” Museum in Los Angeles. In both cases we do see things, but we also fill in things that are not shown as we try to connect with the people represented and their experiences.

In order to understand and balance the many competing motivations we encounter in life and in work, we sample ourselves, making conscious and unconscious decisions about what is expected, when to conform and when to resist norms. Depending upon how tightly structured any given situation is, the stakes of resistance and the impulse to obey conventions increase. “Passing” for a member of a dominant group in a given society has a complex and painful history in relationship to race and the African American experience in particular. White-passing combines bias and the human reliance upon our senses to form an image of others, and it relies upon covering our real identities in order to be included. Straight-passing and gender-passing equally negotiate between individual identity expression and community expectations. In 2007, Kenji Yoshino described the process of intersectional covering, reflecting on the ways in which as a gay, Asian-American lawyer he sampled and covered parts of himself so as to pass as belonging to each of these communities. Eloquently, he finishes his argument suggesting that organizations create a “tragic choice” between identity and inclusion.

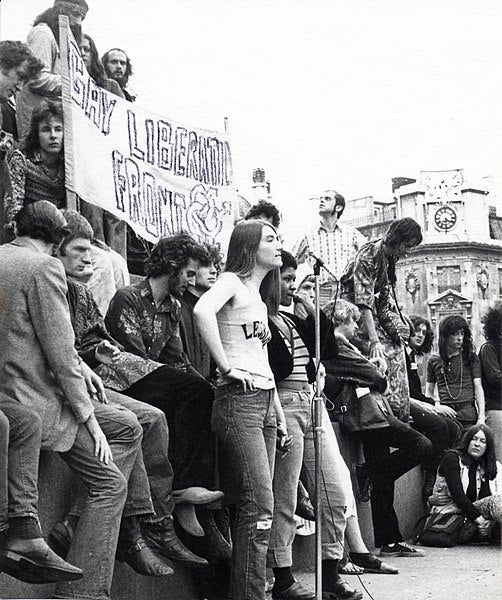

Today, the Victorian pressure to cover up, so as to pass, remains strong for the LGBTQ community. I am writing these thoughts on the 42nd anniversary of the Stonewall Riot in Greenwich Village on 28 June 1969 and on the 41st anniversary of the first gay pride marches a year later. In response not only to that moment but also to systemic oppression and violence, each summer streets and news feeds are filled with exuberant and resilient expressions of gender and sexuality. Wilde paid a dear price in prison for refusing to pass as straight. He was forced to give up his name and his bespoke suits, and he was forced to don Prisoner C.3.3’s uniform. It is worth noting that his perfectly cut dark suits, still expected in many business settings today and never out of fashion, began as a queer gender expression in the dandy culture of the late 18th century. Even a globally recognized professional uniform can create allyship and inclusivity if we let people tailor it for themselves and especially recognize the person who wears it. Otherwise, not only clothes but identities will remain hidden away in the closet, and our communities and organizations will be diminished, as well as less stylish, as a result.

LSE Library, No restrictions, via Wikimedia Commons