The Day After Trauma: Conversations in a Precarious World

Elizabeth Richmond-Garza, PhD

In Partnership with Leslie Dill, HDO’s Business Development & Marketing Coordinator

August 15, 2022

You enter your brick-and-mortar workplace on the morning of September 11, 2001, wondering whether your friends are alive in the devastation of Lower Manhattan and whether your colleagues know what has happened. You receive emails from first-year students in the last week of August 2005, letting you know that they cannot come to class or contact family because of Hurricane Katrina, as you wonder whether your own family in South Louisiana are safe.

You lead an HDO graduate seminar on diversity on November 9, 2016, four days after the US election, knowing that you have very different political views reflected in your group. You check your organization’s Twitter feed on October 16, 2018, and #MeToo is trending as you prepare a lecture for 250 undergraduates on what frightens them. You join your tenth Zoom meeting of the day to work with a capstone student recovering from COVID whom you may never meet in person. You start a meeting on inclusivity mere hours after the protests in support of George Floyd began on May 26, 2020.

What do you say? What do you do? How can you create a space where we can be uncomfortable but not unsafe together? How can we be mindful so that no one feels the need to suppress ideological and personal content through the silence, small talk, and apparent consensus, even if our organizations, communities, and families would like to avoid these conversations? As we get ready to go to work each day, well-intentioned but tone-deaf organizational responses to trauma at best disappoint and at worst exacerbate. Have you ever said to yourself something like…

- I can only imagine what work will be like today. I wish I did not have to go in.

- What kind of emails will I get from the C-suite and HR today, none of which help me process this pain?

- I am just going to pretend nothing happened. Hopefully no one will bring it up.

- I better not say anything, in case I get it wrong.

- I think my coworkers and I are affected by what happened, but I don’t know how to start.

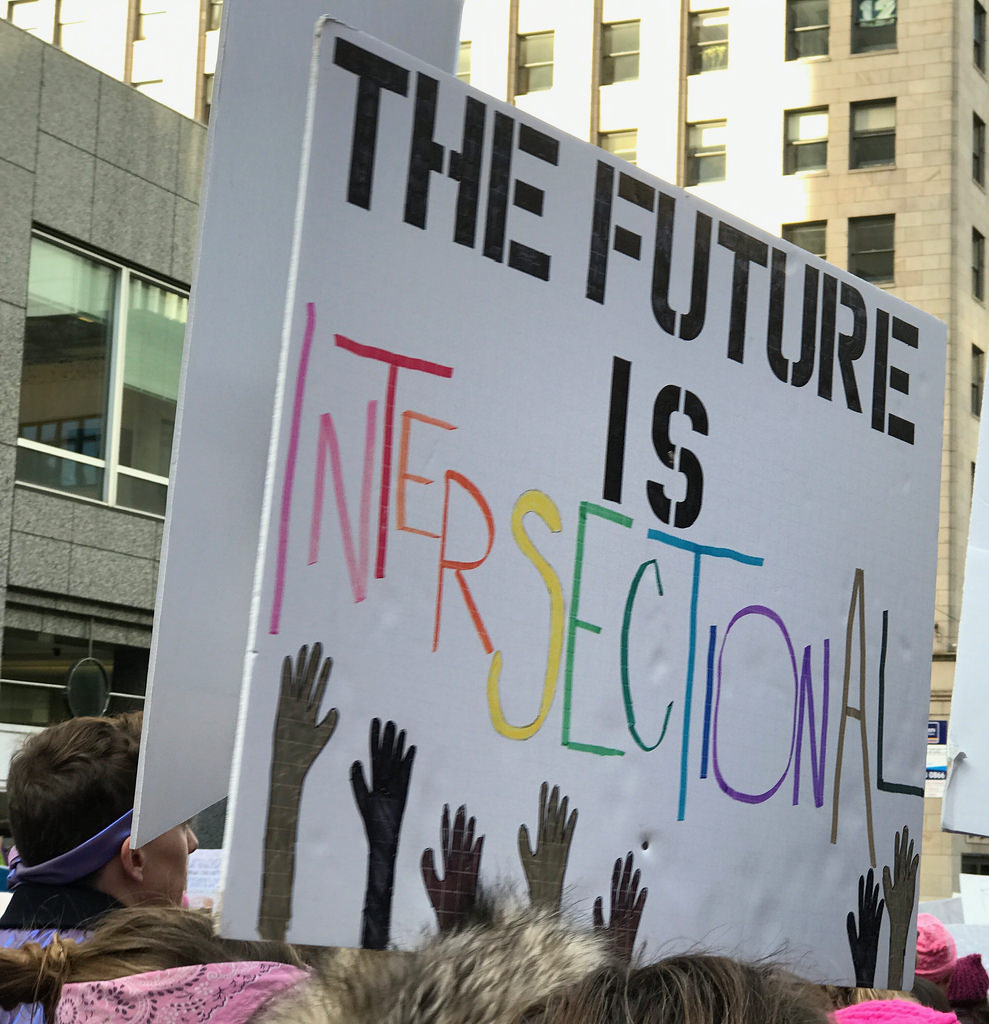

“There is no such thing as a single-issue struggle because we do not live single-issue lives.”

Audre Lorde

Activist, Writer, Professor, Feminist

THE VARIOUS TRAUMAS mentioned above represent only a small, US-oriented array of the shared pain and precarities we have experienced since the turn of the millennium in our polarized communities across the globe. Some are collective while others are personal; some are agreed horrors and others debated; some are single events while others involve sustained suffering; some touch us directly, but ethical trauma related to the harm done to others can be just as affecting.

Sometimes, trauma violates our actual workplaces, houses of worship, or other apparently safe environments, as those of us who work in education are all too aware. To each workday, we bring our experience of individual loss, the scars of unnoticed microaggressions, and triggerable sensitivities of which we may not even be aware. These feelings and responses are core to who we are, and inclusive organizations recognize and accommodate them so as to anticipate how they will respond to the terrible things we know will someday happen.

British-Ghanaian philosopher, Kwame Anthony Appiah’s 2012 challenge asks us to care for those who are not like us. The task I gave myself on each of those days was to help colleagues and students to “converse” with each other. Appiah does not rely upon agreement, does not avoid difficult conversations, nor does he presume that people are without prejudice. Instead, he takes difference and disagreement as givens and invites us to recognize that others value ideas with which we disagree without hiding our own ways of being and moving through the world.

How do we create safe spaces for addressing trauma in the workplace without triggering more conflict and pain? Is it possible to avoid asking people to check their souls at the door? Many of us are given guidance on how to have difficult conversations by our organizations but are also mandated to report certain disclosures, making addressing trauma complex legally and ethically. We are encouraged to be allies, but allyship can be merely performative or place unequal burdens on different individuals. For me, recognition, vulnerability and empathy are key and should be proactively built into the work environment from the start rather than being reactive.

Recognition involves stating the facts (as best I knew them). “Facts” allow space for multiple “truths” depending upon specific values and judgments. Relinquishing my authority to interpret or characterize those facts does not suppress my opinion, but it does involve not explaining or judging to allow varied perspectives to emerge. It also requires the uncomfortable silence, not of avoidance but of reflection. As an educator, I find stepping back from making sense of a situation hard. Vulnerability involves awareness of limitations, including my own. I cannot resolve the trauma or, sometimes, even begin to explain it. I have to sit with the pain and incomprehension.

The final element in starting the conversation is to express regret and empathy, having cultivated trust in advance, before you need to rely upon it. At its core trust relies upon all voices in the working group being supported regardless of direct reporting and accountability flows.

We are encouraged to be allies, but allyship can be merely performative or place unequal burdens on different individuals.

OUR EVERYDAY LIVES entail performing expected roles. Every actor knows that they bring a full and complex identity to the role that they are about to play, but then they select the parts of themselves that suit the scene. They also rehearse their part with the rest of the cast, creating expectations and trust before the curtain goes up. As civil-rights activist Audre Lorde eloquently noted in 1982, our real-world identities are equally complex and intersectional: “There is no such thing as a single-issue struggle because we do not live single-issue lives.”

We thrive in our professional settings when we feel that we belong, that we are seen and valued. Legal scholar Kenji Yoshino, however, has repeatedly addressed the ways in which we “cover” who we are in the workplace. He mourns the ways in which organizational culture promotes sampling over presenting our complete selves and thereby “puts people to this tragic choice between their identity and inclusion” (2014). While we will never fully know another human being, we can enable self-expression, rather than discouraging it, in ways that minimize precarity, respect humanity, and enhance professional lives.

In my workplace, the preferences of an undergraduate in their first semester, a staff colleague and a tenured faculty member should be equally weighed. I simply ask people what they want to do with our time together, including being silent or leaving. I know what approaches would be most sustaining for me personally, but I come prepared to adjust and also to allow each person to do what they think best. Allowing time, both on the day and later, ultimately is appreciated and allows people to succeed in the long run rather than “covering” and shutting down. Empathy, as opposed to sympathy, involves seeing a situation from someone else’s point of view rather than your own. Think about the difference between these two responses to someone feeling harmed:

I know just how you feel and this is what I would do if I were you. Don’t worry you will get over it. I did.

I see that you are experiencing something and I can’t imagine what that is like. Please let me know if there is anything I can do to help, including just giving you space to deal with things.

Given the unpredictable world in which we live, there will always be a need for improvisation and agility. Recognition, vulnerability, and empathy can help us to translate feelings into resilience, whether we are touched directly or wish to be the best possible ally to others.

EMPATHY ALSO ENCOURAGES TRUST, putting people more at ease and allowing them to converse without needing to agree. Only during the immediate Katrina emergency did anyone leave my classes. As the storm passed, those who chose to remain responded differently, both collectively and individually, in each working group. As painful as the topics were, and as opposed as the perspectives even on a natural disaster were, respect and civility were maintained.

On the morning of 9/11, the twenty undergraduates in my class at 9:30 AM CST just wanted to listen to The Strokes, The Yeah Yeah Yeahs, and Jay-Z (we picked them together) and to talk about New York City where some of us had lived. We had only known each other one week, and this is what felt right for people who were still strangers to each other.

After the 2016 election, a group of professional HDO MA students opted to share very openly their divergent thoughts about US politics because they trusted each other and knew that each voice would be heard and not judged. We had been working together for three months intensively. In all cases, we used parts of the reading and homework as examples to help us think through the issues raised.

In 2018, rather than talking directly about sexual abuse and #MeToo, a conversation that would have required too much trust for a large lecture class, the students actually voted to stay with the syllabus. They were more comfortable talking about sexism in Dracula than about their own experiences. Stoker’s fictionality created a safe space to explore the unsafe or to be quiet, knowing that your silence is respected and heard. Sometimes silence is what we all need in the moment.

While each community will have different and unique ways of processing each particular trauma, we can create scripts and trust for ourselves and our colleagues in advance to help us to be fully present in our workplaces, especially in moments of conflict and suffering. Given the unpredictable world in which we live, however, there will always be a need for improvisation and agility. Recognition, vulnerability and empathy can help us to translate feelings into resilience, whether we are touched directly or wish to be the best possible ally to others.

Dr. Elizabeth Richmond-Garza is UT Regents’ and Distinguished Teaching Associate Professor of English at UT Austin. She was the Director of UT’s Program in Comparative Literature from 2001-2022 and was the chief administrative officer of the American Comparative Literature Association from 2002-2011. She is affiliated faculty in the Center for Russian, East European and Eurasian Studies, the Center for Middle Eastern Studies, and the Program in the Human Dimension of Organizations. She holds degrees from UC Berkeley, Oxford University and Columbia University and has held both Mellon and Fulbright Fellowships. She writes on Oscar Wilde, theatre, the gothic, detective stories, and literary theory. She teaches diversity and inclusion through literature and the fine arts and works actively in eight world languages. Richmond-Garza’s multimedia approach to teaching has been honored by a dozen teaching awards both at UT Austin and across the state of Texas.

Dr. Richmond-Garza leads the HDO Professional Seminar, Understanding & Managing Motivations.